Please enjoy this excerpt from Chapter 1 of Interviewing Skills for Auditors, available here.

Objectives:

- Distinguish between types of interviews

- Identify the benefits of establishing rapport during an interview

- Identify the benefits of having a productive, friendly relationship with the client

Always remember the purpose of an interview – to get information. But because you are working with people to get the information you need, you must also build and maintain solid relationships. If you blow an interview by being unfriendly or unprepared, you can damage your entire engagement.

The key is to build rapportwhile getting accurate, insightful information to get your job done. This is easier said than done—as most interviewees view the auditor with a bit of distrust. Most auditees see audits as necessary but unpleasant. Or, they may think they’re totally unnecessary and a waste of time. During a fraud examination, many of the people you interview are likely to be on edge, especially the fraud perpetrator.

In order to succeed as interviewers, we endeavor to:

- Build relationships and rapport

- Conduct focused, meaningful interviews

- Gather strong, accurate, and complete evidence

Building relationships and rapport

Whether you are in the role of auditor or fraud examiner, one of your top priorities is to buildrapportwith the person you are interviewing. Try to forget the good cop/bad cop stuff you see on television or in the movies. You want the interviewee to feel like the two of you have something in common and that they can relate to you. If the person being interviewed does not feel comfortable with you, forget about getting all the information you need. You may get the bare minimum, but no more. If you are really bad as an interviewer, you may lose a client and won’t get positive referrals.

There are some differences between the types of interviews that auditors do versus fraud examiners. Where appropriate, “auditor” and “fraud examination” interviews are discussed separately in the following sections.

Auditors have to work extra hard to gain the trust of the client so that the client will help you do your work—or at least, not act as a barrier to doing your work. Because you are by default in a leadership or controlling position on an audit – the relationship with the client hinges on the auditor’s approach and attitude.

Fraud examiners must also work to establish rapport – even with the “bad guy” (i.e., suspected fraud perpetrator). During a fraud examination, you will interview people who, hopefully, will know what kind of fraud was committed, how it was done, and who did it. Many interviewees will be hesitant to share such information because they are fearful of losing their job or getting in trouble. Depending on how bad the bad guy is, they may fear for their personal safety. You have to interview them in a way that gets them to open up and share what they know and provide you with evidence. When it comes to interviewing the suspected fraud perpetrator, your crowning achievement will be to get a confession. That kind of interview is very different from interviewing potential witnesses. Yet, both types of interviews require rapport.

When conducting all interviews as either auditors or fraud examiners, repeat after me:

Rapport. Rapport. Rapport.

The interviewer as a facilitator

The focus of an audit interview is on the softer, gentler style of interviewing—the facilitated interview.

In a facilitated interview, you have a comfortable, but focused chat with the client. When clients feel safe, they will tell you what you need to know. If clients are untrusting, they will tend to withhold important information or act defensively.

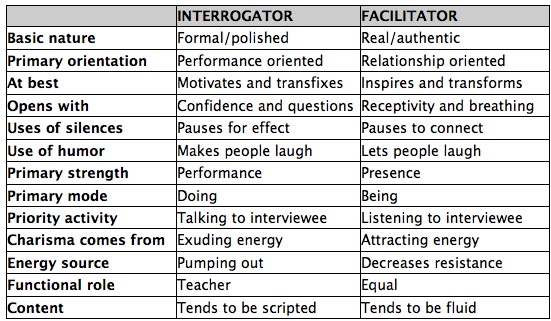

Here is a chart that lays out important characteristics of a facilitated interview for an audit.

As a facilitator, don’t put unnecessary pressure on yourself by expecting every word to be planned before it drops from your authoritative lips! Instead, view the interview as having a more loose and casual agenda that is flexible and open to changes and mid-meeting shifts in topics. This doesn’t mean you completely let go of your agenda, but it does mean you give up needing every moment to be scripted and controlled. Do not go through your list of questions like the list you take to the grocery store. Got to get two cans of tomatoes, one can of corn, and one can of peas because you’re making soup for dinner tonight. Have the mindset that it is OK to leave the canned goods aisle and come back in a few minutes. You’ll still get what you need – and, possibly much more.

Have you ever been audited? I have, three times. It is not fun. It will never be fun. But the auditor can make it tolerable or absolutely unbearable and scary.

I was the controller for two new federal grants and the federal grantor sent an auditor to check me out early in our first year. The auditor called on Mondaymorning and said he was on his way that afternoon. I offered to help him find a good hotel and restaurant, but he would have none of it! When he showed up, he wanted to know where my files were so that he could dig into them at will. I told him that I would provide what he needed upon request.

Over the next week, he hovered at the door of my office and seldom gave me a moment’s peace. He scared the bejesus out of me because he never connected with me as a human being. I can only imagine that he is miserably unhappy when he returns to his empty, desolate, isolated apartment in Washington. I was glad to see him go—but his report, created without any verification, did not make anyone in my office happy. We fought his findings for a good six months before his supervisor agreed to drop them. (This auditor comes up again, later.)

If a CPA firm treated their clients in this manner, they would be fired immediately – or at least not hired to return the next year. CPA firms must treat their clients with respect and kindness, or they will starve! In the government realm, the governmental auditor is in a more obvious position of power, often power that goes unchecked. Unchecked power can result in, at best, a disregard for common courtesies.

Some interviewers seem to have watched too many episodes of crime dramas and they utilize an aggressive, interrogator style. They approach an interview with the sole objective of extracting information regardless of how painful it is for everyone involved. The pressure on an interrogator is enormous, as they must maintain control at all times. This approach to auditing would simply wear me out and make me hate my job.

Here are some characteristics of an interrogator style interviewer:

- Interrogators don’t take time to connect with the interviewee and start with the tough questions right away.

- Interrogators take on the role of the superior and come off as a teacher or authority.

- Interrogators seldom pause, as they are performance oriented and prefer to pump out information.

- Interrogators will have a core objective that they will not compromise.

- Interrogators answer questions in an authoritative way and do not verify that the questioner is satisfied with the answer.

It takes a lot of effort to keep everything under control—and the interrogator is probably not having any fun at all (unless they enjoy making people squirm). The interviewee definitely does not enjoy getting hammered with questions by someone with a superior attitude and aggressive tone.

Interviews don’t have to be unpleasant! The interviewer can take on the role of the facilitator instead. A facilitator contributes structure and process to interactions but is not motivated to entirely control the interaction. A facilitator instead acts as a helper or an enabler.

A facilitator views a meeting as an opportunity to interact and connect as well as gather information. Characteristics of a facilitator style interview include:

- Facilitators take time to connect with the interviewee on a personal level. The facilitator holds back on tough pointed questions until a safe relationship has been established.

- Facilitators acknowledge that they are not as knowledgeable about the interviewee’s work and prefer to work on a peer-to-peer basis.

- Facilitators pause frequently to give the interviewee time to think, breathe, and relax.

- Facilitators have a core objective, but they are open to a change of course and are open to feedback from the interviewee.

- Facilitators explore the reason or source of the interviewee’s questions and make sure they have resolved any uneasiness on the part of the interviewee before they move on.

A facilitator isn’t under pressure to perform or be perfect. They view each interaction with the client as a chance to leave the grind of audit documentation and testing behind and have a pleasant interaction with another professional. This attitude is important for interviewing clerical staff members, too. They are often overworked and unappreciated. If you interview them with an attitude of being on equal footing with you, they will likely open up and provide all the information you need…and, then some.

If a more relaxed approach to interviewing and working with the client and their employees appeals to you—try these ideas on for size:

- At the beginning of each interaction with the client take time to connect on a personal level. Take some time for pleasant chit-chat before you get down to business. You can commiserate over how bad the traffic was getting to work or how bad the weather is. Anything that will help the interviewee think you’re just like them.

- Briefly explain the purpose of the interview. Don’t go all accountant on them and start talking about separation of duties and internal control – not unless you want to see their eyes glaze over. An auditor can say: “I’m here to help with a cash audit that’s part of the overall financial audit done for your firm every year.” Or, a fraud examiner could say, “I’ve been asked to review some of the procedures in hopes of streamlining some processes.” Notice I did not say, “We think $20 million has been stolen.”

- Ask the interviewee if they have any questions for you before you begin your questions.

- Endeavor to understand the source or true purpose of the interviewee’s question(s) and make sure you resolve their question(s) before you move on.

- Acknowledge that you are not an authority on the interviewee’s job; he is. Thank him for helping you do your job and for sharing his authority.

- Ask for the interviewee’s assistance. For example, you can say: “I need to understand the procedures done in this office. Will you help me by describing the steps involved in balancing out your cash drawer?”

- Hold pointed questions for late in the interview in hopes that the interviewee will have revealed the answer to you somewhere along the way.

Watch the client for signs of discomfort or distress and pause to resolve these issues. In this text, we will cover a variety of concepts that will help you feel more confident in building a productive working relationship with the auditee, including:

- How to manage the emotional environment

- How to build trust

- How to maintain your credibility and authority

- How to read body language

- How to respond to questions

Why conduct an interview?

The true and selfish reason you want a friendly relationship with an interviewee is that a friendly interviewee will help you get your job done. For an auditor, your job is to conclude or express an opinion regarding your particular audit objective. In order to do this, you are going to have to gather some evidence. A friendly interviewee will help you gather the evidence you need. An unfriendly one will thwart your efforts and do his best to conceal information. And, they may conceal information – not because they’re guilty of any wrongdoing – it could be just because they do not like you.

A CPA friend of mine once worked in the accounting department at a University. And during one of many audits, an auditor found a $.50 error (yes, that’s 50 cents!) and acted like it was the largest embezzlement in history! The auditor rudely informed the payroll director that they were going to publish a finding regarding the small timecard error that resulted in an overcharge of $.50 to a federal work-study program. The payroll director tried to professionally discuss the concept of materiality, but the government auditor wouldn’t budge. How cooperative do you think the payroll director and other payroll staff members were after that ridiculous exchange? They provided exactly what the federal auditor requested and no more. They answered her questions with a curt “yes” or “no,” and, behind her back, called her “The Ice Princess.”

Interviews can lead you to other evidence or they can act as evidence.

Check out this quote from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO)’s Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards regarding performance audits:

So, an auditor’s job is to evaluate an audit subject against a stated criterion. For instance, a financial auditor will compare the financial statements of his client against generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). If the client meets GAAP (the criteria), the auditor can say so in his or her report. A city internal auditor might evaluate whether the city’s purchasing department meets city regulations regarding technology purchases. The criteria in this case are the city regulations.

How do you, the auditor, know whether the auditee has met the criteria? How can you confidently conclude that the auditee has met the criteria? You have to gather evidence.

Testimonial evidence is the weakest

The AICPA and the GAO discuss three types of evidence.

- Physical

- Documentary

- Testimonial

Let’s say you are doing an inventory audit at a car dealer. An example of physical evidence would be going out on the lot and making sure the cars are there. Documentary evidence would be comparing purchase vouchers to inventory records to make sure the cars are there. Testimonial evidence would be asking the owner of the dealership if the cars exist.

Obviously, the results of an interview cannot be relied upon as the basis for your audit conclusion. They can contribute to your audit conclusion but should be bolstered by some other sort of evidence.

Testimonial evidence—the fancy auditor term for verbal evidence—is the weakest type of evidence. I haven’t met very many bold-faced liars in my work as an auditor, but I have met quite a few auditees who will tell you what you want to hear. You may ask, “Do you sign purchase vouchers?” The auditee may answer, “Yes.” But what he is really thinking, in that invisible bubble above his head is, “I usually sign purchase vouchers, but if I am busy, I don’t get around to it and just move them to Beatrice’s in-box for processing.”

Or, you might ask the wrong person or a person who is not up-to-date in their knowledge. You might ask a manager at a housing project if they got three bids on a repair. But the person who really knows is the maintenance supervisor.

Get in the habit of asking for evidence

The inherent weak nature of testimonial evidence requires that you get in the habit of asking the interviewee for some documentation or physical evidence before you leave the interview.

If the interviewee brings up something significant during an interview, say something like, “What do you have that I can put in my working papers to show my supervisor that you sign the purchase vouchers?” Notice how I softened your statement—I did not say, “I don’t believe you; show me!” I blamed this need for documentation on the supervisor—so it softens up the request, makes it less offensive—but still gets you what you need.

If you forget to do this during the interview, no worries—just call the client back later.

In this text, we will also discuss:

- What constitutes sufficient, appropriate evidence

- How to document your evidence

Conduct focused, meaningful interviews

A bad interview can be a waste of time and frustrating for everyone involved.

Auditors and auditees both complain about long, boring, unfocused meetings. Sometimes this is the result of unfocused, boring, and overly talkative auditees. But more frequently, it is the auditor’s fault.

So, in this text, we will also discuss:

- How to handle difficult interviewees

- How to keep the meeting on track

- How to plan and phrase questions

How the text is organized

Chapter 2: Interviewing Competencies—an overview of the skills that can make you a successful interviewer.

Chapter 3: Relationship Building & Rapport —concepts and skills you need to build a good working relationship and rapport with the interviewee.

Chapter 4: Non-Verbal Communication—how to read the interviewee and exhibit positive, open body language to build trust.

Chapter 5: Asking and Responding to Questions—how to design questions that uncover the information you need. Also included in this chapter is a discussion of how to respond to the interviewee’s questions to enhance and build trust.

Chapter 6: Audit & Investigation Evidence—a review of what the GAO says about audit evidence in the Yellow Book (Government Auditing Standards).

Chapter 7: AU-C Section 240—a review of the auditor’s responsibility to detect fraud and how interviews are integral to fulfilling this responsibility.

Chapter 8: Planning and Scheduling an Interview—considerations in getting ready for an interview.

Chapter 9: Steps to Conducting an Interview—how to structure an interview for maximum effectiveness.

Chapter 10: Listening Skills—an interview isn’t about the interviewer talking, but instead, about paying close attention to the interviewee’s responses and leading the discussion.

Chapter 11: Documenting the Interview—how to make sure your documentation meets standards and your supervisor’s expectations.

Chapter 12: Keeping the Interview on Track—tips and techniques for making sure your interview is purposeful and focused.

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: