Hi Lovely Readers!

I am beginning a book on internal controls… more specifically the GAO’s take on internal controls… and I thought I’d share it with you chapter by chapter as I get them drafted.

Chapter 1

Internal Controls à la GAO’s Green Book

- Identify the purpose of the GAO’s Green Book

- Identify the uses of the GAO’s Yellow Book

| Essential Audit Skills in Los Angeles |

| December 2015 |

| Register here. |

Green Book, Yellow Book … will the Government Accountability Office (GAO) never cease creating books with colored covers? Next thing you know, it will come out with a Purple Book!

The Green Book’s formal title is Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government. The Yellow Book is also known as Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards. Are you sleepy after reading those long titles? If you are like me, you are grateful for the simpler, color-oriented monikers of these important pieces of professional government literature.

The Green Book presents a comprehensive model that professionals can use to both create and audit controls. The latest Green Book was published in 2014 and is available online here: http://www.gao.gov/greenbook/overview.

In this text, we will use the Green Book’s model to design controls over the use of credit cards in a government entity. In early chapters, I occasionally will mention the auditor’s perspective on controls. But we will learn more about controls if we endeavor not just to evaluate controls as auditors do but, instead, to create them from scratch as managers must do. At the end of the book, we will switch gears and look at controls from the auditor’s perspective and design tests of controls.

But before we get too far along with our case study, let’s look at how the Green Book came into being and find out whether your organization should be using it. As we will see, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) bases the Green Book on a model of internal control created by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

The GAO pushed for better controls in 1983.

The GAO is the legislative auditor for the federal government. In addition to auditing federal agencies and reporting the results back to Congress, it also advises executive agencies on how to make government more efficient and effective. The Federal Managers Financial Integrity Act of 1982 requires the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to establish standards for internal controls. The GAO made its first efforts toward creating a standard for internal controls in 1983.

In the opening letter to this first version of the Green Book, the Comptroller General of the GAO said:

In the past decade, numerous situations came to light that dramatically demonstrated the need for controls as the Government experienced a rash of illegal, unauthorized, and questionable acts which were characterized as fraud, waste, and abuse. It is generally recognized that good internal controls would have made the commission of such wrongful acts more difficult. Consequently, increased attention is being directed toward strengthening internal controls to help restore confidence in Government and to improve its operations.

I wonder what the Comptroller General would think of the hijinks in the government realm in the past 30 years!?!

Congress pushed for better controls in 1977, and the Treadway Commission was formed.

Only six years before the Financial Managers Financial Integrity Act, corporate fraud was getting the attention of Congress. In 1977, Congress enacted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) as a result of 400 US corporations admitting that they had made questionable or illegal payments to foreign officials as part of conducting business in other countries. In response, the Treadway Commission, a private-sector initiative, was formed in 1985 to inspect, analyze, and make recommendations on fraudulent corporate financial reporting.

The COSO Report was issued in 1992.

As a result of the Treadway Commission’s initial report, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) was formed. COSO retained Coopers & Lybrand, a major CPA firm, to study the issues and create a report on controls. This report was titled Internal Control – Integrated Framework and was issued in 1992.

As a result of the Treadway Commission’s initial report, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) was formed. COSO retained Coopers & Lybrand, a major CPA firm, to study the issues and create a report on controls. This report was titled Internal Control – Integrated Framework and was issued in 1992.

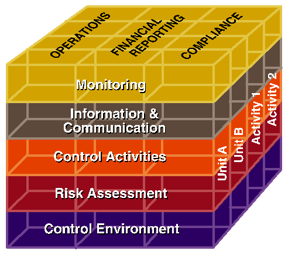

And for the first time, we were introduced to the COSO cube that many of us use in our work today.

Over time, the COSO model, as it came to be called, was integrated into various auditing standards including the American Institute of CPAs auditing standards, the GAO’s Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (the aforementioned Yellow Book), and the Institute of Internal Auditor’s professional literature.

The COSO model evolved.

The COSO model evolved.

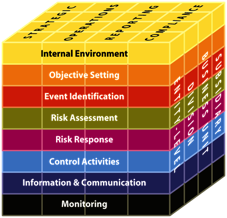

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) didn’t just accept the COSO model as is: in 2004, they added to and enhanced the model and renamed it the Enterprise Risk Model. We will look at the Enterprise Risk Model in more detail later because it has some features that will help us understand the risk assessment portion of the Green Book.

SOX renewed interest in the COSO model in 2002

After a pate of corporate financial scandals (Enron, Worldcom, etc.) at the turn of the century, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (frequently referred to as SOX) in 2002. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires that publically traded companies in the United States certify that their internal controls over financial reporting are effective. Most corporations used the COSO model as the framework to guide this assessment.

The COSO model and report were revised in 2013.

The COSO model and report were revised in 2013.

The COSO model was revised in 2013, more than 20 years after its initial creation. The 2013 revision didn’t alter the cube very much; the side of the cube now uses the term “division” instead of “unit,” and a few titles were changed on the face of the cube: “financial reporting” on the top of the original cube was changed to the more broad “reporting,” and “monitoring” was changed to “monitoring activities.” The side of the cube now uses the term “division” instead of “unit.”

These changes are minor compared to what COSO did to the text of the report. The original 1992 COSO report was presented in narrative form using lengthy complex paragraphs. The 2013 version breaks each of the five elements on the face of the cube into 17 principles, and then these principles are further broken into 81 points of focus. Breaking down the narrative into smaller, more digestible concepts makes the document much easier to scan and, thus, to use.

The 2013 version of the COSO model is available here http://www.cpa2biz.com/AST/Main/CPA2BIZ_Primary/InternalControls/COSO/PRDOVR~PC-990027/PC-990027.jsp for $99-270, depending on whether you want a piece of the document or the entire set of literature.

The GAO published the Green Book in 2014.

In September 2014, the GAO revised the Green Book. The 2014 version replicates the 2013 version of the COSO model but changes some terminology to customize the model for the government environment.

Is the Green Book required?

So now that you know the history of the Green Book, we can address whether you have to use it. And to understand that, we need to know whom you work for.

If you work for a federal executive agency, your agency is required by the Financial Manager’s Financial Integrity Act to report each year on the status of internal controls. And the Green Book is the benchmark that your agency is likely to use in this evaluation. However, federal agencies are not required to ensure that their controls meet every internal control standard described in the Green Book.

If you are a grantee, you should consider the following paragraph from the Uniform Administrative Rules, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Grants issued in 2014 (bolded print added):

200.303 Internal Controls

The non-Federal entity must:

(a) establish and maintain effective internal control over the Federal award that provides reasonable assurance that the non-Federal entity is managing the Federal Award in compliance with federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the federal award. These internal controls should be in compliance with guidance in “Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government” issued by the Comptroller General of the United States and the “Internal Control Integrated Framework” issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

Notice that the introductory clause to that paragraph says “must,” and then, within section (a), it says the non-federal entity (read that as grantee) “should” be in compliance with the Green Book. Now the combo of this “must” and “should” statements may make you think, as I did when I first read it, that grantees must apply the Green Book in designing and implementing their internal controls.

But per a question and answer document from COFAR (Council on Financial Assistance Reform, who are the creators of the Uniform Administrative Rules, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards), the word “must” does not apply to that sentence about the Green Book. Only the word “should” does. And to the federal government, “should” is not mandatory but, instead, simply a best practice.

Are you confused? Join the club! Often it seems like the federal government’s job is to prevent intelligent humans from comprehending their writing. The bottom line is that in the government realm, the Green Book is used as a benchmark for controls, not a mandatory requirement for controls.

COSO is a little stricter

I feel I should repeat a few things before I show you a bold statement from the COSO organization. First of all, please remember that COSO is not the same entity as the GAO. And the GAO borrows the COSO model to create the Green Book but does not go along with everything COSO says.

Secondly, it is very unlikely that COSO has any authority over you. For it to apply, your organization, or the standard-setting body to which your organization adheres, must adopt the COSO internal control model.

For instance, if you are a publically traded corporation and subject to the Sarbanes Oxley Act, you might have adopted COSO as your control model. But a publically traded corporation may have easily adopted another control model, like COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology).

Or, if you are an audit organization following the AICPA auditing standards, you are required to use the COSO model to evaluate internal controls. But this does not mean that the audit client is required to apply it in the creation of their internal controls.

Now that I have made it clear that this is a statement from COSO and not the GAO and that COSO likely has no authority over your controls, here is that high and mighty sentence from the 2013 COSO Executive Summary:

When a major deficiency exists with respect to the presence and functioning of a component or relevant principle, or with respect to the components operating together in an integrated manner, the organization cannot conclude that it has met the requirements for an effective system of internal control.

My mouth fell open when I read that sentence! (And yes, it is one sentence if you thought about checking it again.) That long sentence sets a very high bar as you will see when you travel through this book.

If you are like most people, the internal controls described in the Green Book are more than a little overwhelming and years away from being a reality in your organization. As you read the rest of this text, I suggest that you imagine the day when the Green Book makes a similarly bold statement and think about whether you could meet that expectation.

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: