Objectives:

• Differentiate between the concepts of materiality and significance

• Identify factors that affect audit risk in a performance audit

• Define the parameters of an audit project: audit objective, audit scope, and audit methodology

• Distinguish among the types of information that you “should” and “may” gather during the planning phase of a performance audit

• Distinguish among the types of evidence and judge their relative strength

• Distinguish between mandatory and optional documentation requirements

When I teach a seminar, I give every student a copy of chapter 8 of the Yellow Book and we refer to it as frequently as possible. It is full of wisdom and helpful tips and more than a few humorous quotes.

I don’t think the GAO means these things to be funny, but they still make me laugh.

My favorite is “having a large volume of evidence does not compensate for it being stupid.” OK, I am paraphrasing, but that is really what they are driving at when they say “8.102d Having a large volume of evidence does not compensate for a lack of relevance, validity, or reliability.”

Why Are the Performance Standards So Long?

The GAO covers audit planning and documentation in what I think is glorious detail in the performance audit chapters. The two performance audit chapters are 56 pages long while the financial audit standards are only 17 pages long!

The financial audit standards and the attestation standards assume you are also applying the AICPA standards for financial audits and attestation engagements, the performance audit chapters do not. The Yellow Book performance audit chapters (chapters 8 & 9) are written from scratch and do not lean on any other document to make key points.

I could spend 200 pages talking about each of our major topics – the three that we covered in the last chapters (internal controls, reportable conditions, and findings) and the two we are going to cover here (audit planning and documentation) – but that would be overwhelming! So instead of making this the 800-page Yellow Book Interpreted (I bet that would sell millions, eh?) I am going to continue lightly covering each topic.

Most of the remaining significant topics are mentioned in this one clause.

Most of the topics we need to discuss in this chapter are summarized in clause 8.35, the clause that describes what auditors include in their planning documentation:

Preparing a Written Audit Plan

8.33 Auditors must prepare a written audit plan for each audit. Auditors should update the plan, as necessary, to reflect any significant changes to the plan made during the audit.

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

a. the proposed audit objectives are likely to result in a useful report;

b. the audit plan adequately addresses relevant risks;

c. the proposed audit scope and methodology are adequate to address the audit objectives;

d. available evidence is likely to be sufficient and appropriate for purposes of the audit; and

e. sufficient staff, supervisors, and specialists with adequate collective professional competence and other resources are available to conduct the audit and to meet expected time frames for completing the work.

In that list, the GAO highlights these major topics:

- Topic #1: Objective, scope, and methodology (8.35 a & c)

- Topic #2: Significance and risk (8.35 b)

- Topic #3: Audit evidence (8.35 d)

- Topic #4: Team competence (8.35 e)

I also want to add two additional topics that are not listed in this clause but take up quite a few pages in the performance audit standards:

- Topic #5: Understanding the nature and profile of the program

- Topic #6: Audit documentation

And we will discuss each of these in turn, but in brief!

Major Topic #1: Objective, Scope, and Methodology

On a performance audit, you formally define and document what the audit is – and almost as importantly – what it is not! Many of our report users erroneously believe that when we audit, we are looking at everything.

Let’s say we are auditing federal funding for school lunches. In this case, the users might assume that we are auditing every aspect of school lunches including whether the lunch employees are following food safety rules, whether the staff is receiving a fair wage, and that cash is deposited each afternoon. And, because there is no way an auditor has the time or the will to look at all of that, we must constantly let the users of our audit work know what we did and what we did not do.

The objective and scope define what you are auditing in relationship to everything that you could be auditing. The methodology tells reader what techniques you used to answer the objective.

The objective, scope, and methodology must be included in the working papers and the audit report. And as we see from the planning memo requirements, there is a relationship between the objective, scope, and methodology. The audit objectives shape the scope and methodology (as well as most everything else on an audit!). Objectives are mentioned a whopping 163 times in chapter 8 of the Yellow Book!

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

a. the proposed audit objectives are likely to result in a useful report;

c. the proposed audit scope and methodology are adequate to address the audit objectives;

More on Objectives

An objective is the question the audit will answer. Auditors call the answer to the objective a ‘conclusion’ or an ‘opinion.’

Let’s say you narrowed your objective regarding the school lunches to “Do low-income school children receive lunch each weekday?” The conclusion could be “No, the low-income children did not receive lunch each weekday.”

8.08 The audit objectives are what the audit is intended to accomplish. They identify the audit subject matter and performance aspects to be included. Audit objectives can be thought of as questions about the program that the auditors seek to answer based on evidence obtained and assessed against criteria. Audit objectives may also pertain to the current status or condition of a program. The term program as used in GAGAS includes processes, projects, studies, policies, operations, activities, entities, and functions.

9.11 Auditors should communicate audit objectives in the audit report in a clear, specific, neutral, and unbiased manner that includes relevant assumptions. In order to avoid potential misunderstanding, when audit objectives are limited but users could infer broader objectives, auditors should state in the audit report that certain issues were outside the scope of the audit.

More on Scope

Scope is the boundary around your work. An old version of the Yellow Book defined scope as “the definition of the relationship between the audit universe and what you actually audited.” I loved that definition, but sadly, it isn’t in the Yellow Book anymore.

Here is what the definition of audit scope in the 2018 version of the Yellow Book:

8.10 Scope is the boundary of the audit and is directly tied to the audit objectives. The scope defines the subject matter that the auditors will assess and report on, such as a particular program or aspect of a program, the necessary documents or records, the period of time reviewed, and the locations that will be included.

9.12 Auditors should describe the scope of the work performed and any limitations, including issues that would be relevant to likely users, so that report users can reasonably interpret the findings, conclusions, and recommendations in the report without being misled.

For our imagined objective – we might define scope as “student lunches served at Daisy Hill Elementary from September 2017-October 2017.”

More on Methodologies

Methodologies are the techniques you use to answer the objectives. For example, to determine whether low-income children are receiving their lunch, you might observe lunch being served, interview the students, parents, and teachers, and examine records of lunches served.

8.11 The methodology describes the nature and extent of audit procedures for gathering and analyzing evidence to address the audit objectives. Audit procedures are the specific steps and tests auditors perform to address the audit objectives.

The audit methodology section of the audit report can get quite detailed as the GAO expects the following components to be addressed:

• Evidence gathered

• Analysis techniques

• Description of procedures performed

• Significant assumptions

• Description of comparative techniques applied

• Criteria used

• Sampling design and whether results can be projected to the whole population

9.13 In describing the work performed to address the audit objectives and support the reported findings and conclusions, auditors should, as applicable, explain the relationship between the population and the items tested; identify entities, geographic locations, and the period covered; report the kinds and sources of evidence; and explain any significant limitations or uncertainties based on the auditors’ overall assessment of the sufficiency and appropriateness of the evidence in the aggregate.

9.14 In reporting audit methodology, auditors should explain how the completed audit work supports the audit objectives, including the evidence-gathering and evidence-analysis techniques, in sufficient detail to allow knowledgeable users of their reports to understand how the auditors addressed the audit objectives. Auditors should identify significant assumptions made in conducting the audit; describe comparative techniques applied; describe the criteria used; and, when the results of sample testing significantly support the auditors’ findings, conclusions, or recommendations, describe the sample design and state why the design was chosen, including whether the results can be projected to the intended population.

Example of an Objective, Scope, and Methodology

Here is an example of an objective, scope, and methodology section from a vintage legislative auditor report. Sorry, I couldn’t find one about school lunches!

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

Objectives

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether the Health and Human Services Commission (Commission):

• Is accurately reporting its performance measures to the Automated Budget and Evaluation System of Texas (ABEST).

• Has adequate controls in place over the collection, calculation, and reporting of its performance measures.

Scope

The scope of this audit included eight key performance measures the Commission reported for fiscal year 2010 and five key performance measures the Commission reported for the first two quarters of fiscal year 2011.

Methodology

The audit methodology consisted of selecting eight key performance measures for fiscal year 2010 and five key performance measures for the first two quarters of fiscal year 2011, auditing reported results for accuracy and adherence to performance measure definitions, evaluating controls over performance measure calculation processes, testing documentation, and assessing the reliability of the data obtained from Commission information systems that support performance measure data.

The Commission completed questionnaires related to its performance measure process to help auditors identify preliminary control information.

Auditors assessed the reliability of Commission data by (1) determining population completeness and reasonableness, (2) reviewing queries used to generate data and data flow processes related to the calculation of the performance measures, (3) performing logical access control testing, and (4) interviewing Commission employees knowledgeable about the data and systems. In addition, auditors traced a random sample of performance measure data from reports to documentation. Auditors determined that the data was sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this audit.

Information collected and reviewed included the following:

• Documentation supporting the Commission’s calculation of each performance measure tested.

• Performance measure data stored in multiple information systems, databases, and spreadsheets.

• Program code for key performance measure calculations.

• Selected business rules for the Commission’s Premium Payables System.

• Available Commission policies and procedures.

Procedures and tests conducted included the following:

• Interviewing Commission staff to gain an understanding of the processes the Commission uses to calculate performance measures.

• Evaluating the sufficiency of policies and procedures to determine whether they were adequate to help ensure the correct calculation of performance measures.

• Auditing performance measure calculations for accuracy and to determine whether they were consistent with the methodology on which the Commission; the Legislative Budget Board; and the Governor’s Office of Budget, Planning and Policy agreed.

• Analyzing data flow to evaluate whether proper controls were in place.

• Testing a sample of documentation to verify the accuracy of reported performance.

• Reviewing queries used to generate data and data flow processes related to the calculation of the performance measures.

• Testing business rules for the Commission’s Premium Payables System and verifying the risk group assignments for a sample of recipients.

• Performing logical access control testing.

• Assessing performance measure results in one of four categories: certified, certified with qualification, inaccurate, and factors prevented certification.

Criteria used included the following:

• Guide to Performance Measure Management (State Auditor’s Office Report No. 06-329, August 2006).

• ABEST performance measure definitions.

• Commission policies and procedures.

• Performance Measure Reporting in ABEST (Legislative Budget Board Report, December 2009).

Major Topic #2: Risk and Significance

As I mentioned, we auditors simply do not have the time (or the will!) to look at everything. Yes, it would be interesting to audit food safety and quality in the cafeteria. I know I ate some questionable items when I was in school (turkey Tetrazzini for one…) and I would like to prevent school lunch suffering for all school children!

But because we don’t want to spend the rest of our lives auditing the school, we decided to focus on whether low-income children receive lunches every school day. In order to get to that narrow objective, we would have prepared a risk assessment to point us at what really matters. (Sorry, kids, a risk assessment tells us that whether you enjoy what is being served is not as important as whether you are getting served at all.)

Here is what the planning memo requires:

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

b. the audit plan adequately addresses relevant risks;

Another term that the GAO uses for the ‘relevant risks’ mentioned in 8.35b is ‘significance’. The term that financial auditors use for ‘relevant risks’ is ‘material.’ Same concept – different subject matters. Material implies that the subject matter is financial. Our chosen objective – whether low-income children receive lunch – is not financial in nature and therefore the term “significant” is more appropriate.

8.15 The concept of significance assists auditors throughout a performance audit, including when deciding the type and extent of audit work to perform, when evaluating results of audit work, and when developing the report and related findings and conclusions. Significance is defined as the relative importance of a matter within the context in which it is being considered, including quantitative and qualitative factors. Such factors include the magnitude of the matter in relation to the subject matter of the audit, the nature and effect of the matter, the relevance of the matter, the needs and interests of an objective third party with knowledge of the relevant information, and the matter’s effect on the audited program or activity. Professional judgment assists auditors when evaluating the significance of matters within the context of the audit objectives. In the performance audit requirements, the term significant is comparable to the term material as used in the context of financial statement engagements.

The GAO Isn’t Very Clear When It Comes to Risk Assessment

The GAO is surprisingly unspecific when it comes to advising auditors on how to conduct a risk assessment. The AICPA is clearly the leader when it comes to defining the concepts necessary to perform a risk assessment such as inherent risk and control risk. The GAO only hints at those terms in the performance audit standards.

Most audit teams I work with go through the following steps as they are conducting a risk assessment:

1. Identify possible audit subjects

2. Ask and document what is significant about each audit subject and what could go wrong. The AICPA calls this step the ‘inherent risk assessment’

3. Refine the audit objective to focus on significant subject matters.

4. Determine what controls the auditee has in place regarding the refined audit objective and evaluate whether these controls are adequate to keep the inherent risk from occurring. The AICPA calls this step the ‘control risk assessment’

5. Design a response to the risks identified.

Instead of mandating those steps and using the terms ‘inherent risk’ and ‘control risk’, the GAO presents this thick paragraph, which it has not altered in over a decade:

8.16 Audit risk is the possibility that the auditors’ findings, conclusions, recommendations, or assurance may be improper or incomplete as a result of factors such as evidence that is not sufficient or appropriate, an inadequate audit process, or intentional omissions or misleading information because of misrepresentation or fraud. The assessment of audit risk involves both qualitative and quantitative considerations. Factors affecting audit risk include the time frames, complexity, or sensitivity of the work; size of the program in terms of dollar amounts and number of citizens served; adequacy of the audited entity’s systems and processes for preventing and detecting inconsistencies, significant errors, or fraud; and auditors’ access to records. Audit risk includes the risk that auditors will not detect a mistake, inconsistency, significant error, or fraud in the evidence supporting the audit. Audit risk can be reduced by taking actions such as increasing the scope of work; adding specialists, additional reviewers, and other resources to conduct the audit; changing the methodology to obtain additional evidence, higher-quality evidence, or alternative forms of corroborating evidence; or aligning the findings and conclusions to reflect the evidence obtained.

While the term ‘inherent risk’ is not specifically included in that paragraph, the nature of inherent risks is: “Factors such as the time frames, complexity, or sensitivity of the work; size of the program in terms of dollar amounts and number of citizens served.”

And while the term “control risk” is not specifically included in the paragraph, the nature of control risk is: “adequacy of the audited entity’s systems and processes to detect inconsistencies, significant errors, or fraud.”

And designing the response to inherent and control risks is addressed in the last, long sentence. You respond to the assessed inherent and control risks by increasing the scope of the work, adding experts, changing the methodology, and enhancing the evidence. The AICPA literatures calls this ‘detection risk’ and acknowledges that it is the only risk that the auditor gets to control; inherent risk and control risk are controlled by the auditee.

Major Topic #3 Evidence

Once you know what you want to audit, you need to ask yourself whether the evidence you need to support your conclusions and findings is available. Here again is where evidence is mentioned in the components of a planning memo in section 8.35:

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

d. available evidence is likely to be sufficient and appropriate for purposes of the audit.

I have heard some auditors refer to this step as “assessing auditability.” If you can see from the outset that it will be hard to audit a particular area, then maybe you should drop it and move on to another audit subject or objective.

8.79 If auditors believe it is likely that sufficient, appropriate evidence will not be available, they may revise the audit objectives or modify the scope and methodology and determine alternative procedures to obtain additional evidence or other forms of evidence to address the current audit objectives.

Our Assurance Statement in the Audit Report Centers around Evidence

Auditors are not political pundits on CNN or FOX News, we are not consultants who give ‘advice’ on what to do to improve results! Auditors, blessedly, base everything we say in fact. When we are finished with our audit, we conclude or opine against our audit objective.

And when we conclude or opine, we are, in essence, making a promise; we are promising that the subject matter meets the given criteria (in other words, we answer the objective) and we are promising that we did not pull our conclusion or opinion out of thin air, but that we backed up our conclusion or opinion with evidence.

Performance auditors must include the promise in the second paragraph of 9.03 in the audit report. Notice the second and third sentence of the second paragraph both refer to evidence!

9.03 When auditors comply with all applicable GAGAS requirements, they should use the following language, which represents an unmodified GAGAS compliance statement, in the audit report to indicate that they conducted the audit in accordance with GAGAS:

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Let’s talk about the concept of appropriateness of evidence first and then address sufficiency of evidence.

Appropriateness of Evidence

It is amazing how often the working papers are filled with evidence that isn’t relevant to the audit objective!

8.91 In assessing the appropriateness of evidence, auditors should assess whether the evidence is relevant, valid, and reliable.

8.102 Appropriateness is the measure of the quality of evidence that encompasses the relevance, validity, and reliability of evidence used for addressing the audit objectives and supporting findings and conclusions.

a. Relevance refers to the extent to which evidence has a logical relationship with, and importance to, the issue being addressed.

b. Validity refers to the extent to which evidence is a meaningful or reasonable basis for measuring what is being evaluated. In other words, validity refers to the extent to which evidence represents what it is purported to represent.

c. Reliability refers to the consistency of results when information is measured or tested and includes the concepts of being verifiable or supported. For example, in establishing the appropriateness of evidence, auditors may test its reliability by obtaining supporting evidence, using statistical testing, or obtaining corroborating evidence.

d. Having a large volume of evidence does not compensate for a lack of relevance, validity, or reliability.

Section 8.102 d. makes me laugh. I remember working for an auditor who was 20 years my senior. He didn’t like how thin my working papers were. (Yes, we were still working with paper!) The file folder didn’t have enough heft, and he told me to beef it up and make it weigh more because he didn’t want to send such a thin folder through the review process.

So, I copied everything I could get my hands on that related to the audit and added it to the folder. And, although the nature and strength of the evidence didn’t change one bit, he was pleased and sent it the fattened files up the chain for further review. What a good use of taxpayer money and trees, eh?

Three Types of Evidence

Related to the concept of appropriateness of evidence are the evidence types. The GAO recognizes three types of evidence:

• Physical

• Documentary

• Testimonial

8.104 In terms of its form and how it is collected, evidence may be categorized as physical, documentary, or testimonial. Physical evidence is obtained by auditors’ direct inspection or observation of people, property, or events. Such evidence may be documented in summary memos, photographs, videos, drawings, charts, maps, or physical samples. Documentary evidence is already existing information, such as letters, contracts, accounting records, invoices, spreadsheets, database extracts, electronically stored information, and management information on performance. Testimonial evidence is obtained through inquiries, interviews, focus groups, public forums, or questionnaires. Auditors frequently use analytical processes, including computations, comparisons, separation of information into components, and rational arguments, to analyze any evidence gathered to determine whether it is sufficient and appropriate. Evidence may be obtained by observation, inquiry, or inspection. Each type of evidence has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Let’s say that you are trying to prove that the low-income children are receiving lunch every school day. What could you do to gather physical evidence? You could install a camera in the lunchroom. You could hire a very tiny adult to pose as a child and have them try to get a free lunch, or you could sit at the cash register in the cafeteria and observe who gets a free lunch. I didn’t say all of these were good ideas – just ideas!

What would documentary evidence look like? You could examine the records that the school maintains on low-income children and you could review the procedures regarding giving out free lunches. You could compare unpaid transactions on the cash register tape to the roster of low-income students.

What would testimonial evidence look like? You could call the parents of the children to ask them whether their children get free lunch. You could ask the cafeteria staff if they provide free lunches.

What type of evidence is best really depends on your audit objective and how much you want to spend on the effort. Physical evidence is often expensive because you must be present (and sometimes travel) to see the evidence. Examining documents may be more efficient but sometimes less reliable.

The Dark Side of Evidence

Each type of evidence has what I call a “dark side.” The dark side of testimonial evidence is as big as that galaxy far, far away; the interviewee can change their testimony at any time and leave you with no support for your audit report. Documentary evidence can be forged.

Physical evidence has a dark side, too. For instance, to gather physical evidence you could sit in the cafeteria and observe the free lunches being doled out. However, the cafeteria staff could just be on good behavior while you are observing because they know you are watching!

In order to compensate for these dark sides, you have to gather “enough” evidence. One piece of evidence usually cannot stand alone. This is where the concept of ‘sufficiency’ of evidence comes in to play.

Sufficient Evidence

While appropriateness of evidence is about its quality, sufficiency is about its quantity. If we are working to support a significant assertion or conclusion in our report, we need more than one piece of evidence.

8.99 Sufficiency is a measure of the quantity of evidence used to support the findings and conclusions related to the audit objectives.

8.92 In determining the sufficiency of evidence, auditors should determine whether enough appropriate evidence exists to address the audit objectives and support the findings and conclusions to the extent that would persuade a knowledgeable person that the findings are reasonable.

When I teach basic audit skills to new auditors, they often ask me, “How much evidence is enough?” And I can’t answer them because “enough” is subjective. I tell them that when I decide if I have enough evidence, I imagine a little drama. I imagine that I’m telling a contentious board something unpleasant that they don’t want to do anything about.

I imagine one of the imagined board members hissing, “You are wrong! We didn’t do that. Prove it!”

And at that point, with a heroic flourish I pull out my working papers and say, “I know I am right because of this evidence, and this evidence, and this evidence…” If I feel confident imagining myself in that situation, I know I have enough evidence.

Some auditors call confidence in the evidence the “warm, fuzzy feeling.” The GAO calls the “warm and fuzzy feeling” “professional judgment.”

My professional judgment will differ from yours. What I deem to be enough will be different than what you deem to be enough, and there is nothing wrong with that! That is natural and to be expected.

Also, don’t be surprised if, as your working papers go through the review process, a working paper reviewer asks you to back up your conclusion and findings with more evidence because in their professional judgment the evidence isn’t strong or enough. Also, natural and to be expected.

Triangulation of Evidence

Have you ever heard of the concept of evidence triangulation? I am afraid one of my supervisors made it up! But it is helpful to keep in mind when talking about the robustness of evidence.

The tips of the triangle represent the sources of your evidence. Each source should be different. If you are inquiring about the school lunches, you don’t want to get all of your evidence from the same guy or gal, especially a guy or gal who is very interested in making sure you don’t see anything suspicious. So you don’t go to the lunchroom manager for all of your evidence. This would make for a flat triangle!

It is best if you can gather evidence from someone outside the process, too. So the triangle reminds you to try to get evidence from three different sources (the three points of the triangle) and that at least one of these sources should be someone who is free to tell the truth.

For instance, I worked with a state agency that was responsible for ensuring that gas station owners remediated gas tanks. “Remediation of gas tanks” is a fancy way of saying that if a gas station shut down, the owner had to properly dispose of the tank and clean the surrounding soil.

The gas station owners didn’t want to pay for the proper remediation of the gas tank, so they did everything they could to mislead the state. Gas station owners would alter site plans, fake engineering studies, and fake moving invoices. Some owners even dug up the ground to make it look like they moved the tank when it was actually still 100 feet away on the other side of the property! Asking the owner for all of the evidence created a flat triangle.

So the auditors got in the habit of asking neighbors about activity in the area. If a dishwasher behind a neighboring restaurant told them that he saw the owner move the tank, the auditor got the evidence he was looking for and strengthened his triangle. Auditors also occasionally contacted the moving companies and engineers directly to verify the move and that the engineering study was actually performed.

8.96 When auditors use information that audited entity officials provided as part of their evidence, auditors may find it necessary to test management’s procedures to obtain assurance, perform direct testing of the information, or obtain additional corroborating evidence. The nature, timing, and extent of the auditors’ procedures will depend on the significance of the information to the audit objectives and the nature of the information being used. Using a risk-based approach, auditors may consider additional procedures if they become aware of evidence that conflicts with that provided by management. In their overall assessment, auditors may document how they resolved situations involving conflicting evidence.

8.014

e. Testimonial evidence obtained from an individual who is not biased and has direct knowledge about the area is generally more reliable than testimonial evidence obtained from an individual who is biased or has indirect or partial knowledge about the area.

f. Evidence obtained from a knowledgeable, credible, and unbiased third party is generally more reliable than evidence obtained from management of the audited entity or others who have a direct interest in the audited entity.

Overall Assessment of Evidence

When you are down in the weeds, auditing against your audit program and planned procedures, you can lose sight of your ultimate goal as an auditor. The ultimate goal is to use strong, convincing evidence to support your conclusion.

More than once, I got to the end of my audit and realized there was a huge hole in my logic and evidence. Luckily, I didn’t announce to my supervisor or my client that I was finished, and I went back and closed up the hole with a few more procedures.

Once I even had to pare down my objective because I had consumed my entire budget and had no more time to gather more evidence.

Knowing this can happen to an auditor, the GAO reminds us to step back and perform an overall assessment of evidence before we close the audit and publish the report:

8.108 Auditors should perform and document an overall assessment of the collective evidence used to support findings and conclusions, including the results of any specific assessments performed to conclude on the validity and reliability of specific evidence.

8.109 When assessing the overall sufficiency and appropriateness of evidence, auditors should evaluate the expected significance of evidence to the audit objectives, findings, and conclusions; available corroborating evidence; and the level of audit risk. If auditors conclude that evidence is not sufficient or appropriate, they should not use such evidence as support for findings and conclusions.

8.115 Additional procedures that could address limitations or uncertainties in evidence that are significant to the audit findings and conclusions include

a. seeking independent, corroborating evidence from other sources;

b. redefining the audit objectives or the audit scope to eliminate the need to use the evidence;

c. presenting the findings and conclusions so that the supporting evidence is sufficient and appropriate and describing in the report the limitations or uncertainties with the validity or reliability of the evidence, if such disclosure is necessary to avoid misleading the report users about the findings or conclusions; and

d. determining whether to report the limitations or uncertainties as a finding, including any related significant internal control deficiencies.

Major Topic #4: Staff Competence

Obviously, you can’t perform an audit with a team that doesn’t know how! In past issues of the Yellow Book, the GAO has been pretty quiet and vague about what makes a good audit team. But guidance regarding audit team roles and responsibilities are peppered throughout the 2018 Yellow Book.

Remember the components of a planning memo? Here is the relevant clause regarding audit team know-how:

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

e. sufficient staff, supervisors, and specialists with adequate collective professional competence and other resources are available to conduct the audit and to meet expected time frames for completing the work.

In the quality control review chapter, we covered the roles of a reviewer, a supervisor, and a monitor. We talked about the qualities of a competent team in the chapter on competence.

I have one more quote from the Yellow Book to share with you regarding a team’s roles and responsibilities. It isn’t the most specific and helpful quote, but I would still feel remiss if I didn’t point it out to you.

4.09 The audit organization and engagement teams may consider the levels of proficiency needed for each role on the engagement when assigning auditors to the engagement.

4.10 Roles on the engagement generally include the following:

a. Nonsupervisory auditors: Auditors in these roles plan or perform engagement procedures. Work situations for these auditors are characterized by low levels of ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty. The nonsupervisory auditor role necessitates at least a basic level of proficiency.

b. Supervisory auditors: Auditors in these roles plan engagements, perform engagement procedures, or direct engagements. Work situations for these auditors are characterized by moderate levels of ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty. The supervisory auditor role necessitates at least an intermediate level of proficiency.

c. Partners and directors: Auditors in these roles plan engagements, perform engagement procedures, or direct or report on engagements. Partners and directors may also be responsible for reviewing engagement quality prior to issuing the report, for signing the report, or both. Work situations for these auditors are characterized by high levels of ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty. The partner and director role necessitates an advanced level of proficiency.

Components of an Audit Plan, Redux

Let’s look back at the requirements for a written audit plan

We have covered all of the topics in the list imbedded in 8.35:

a. objectives

b. risk

c. scope and methodology

d. evidence

e. staffing

Preparing a Written Audit Plan

8.33 Auditors must prepare a written audit plan for each audit. Auditors should update the plan, as necessary, to reflect any significant changes to the plan made during the audit.

8.35 A written audit plan provides an opportunity for audit organization management to supervise audit planning and to determine whether:

a. the proposed audit objectives are likely to result in a useful report;

b. the audit plan adequately addresses relevant risks;

c. the proposed audit scope and methodology are adequate to address the audit objectives;

d. available evidence is likely to be sufficient and appropriate for purposes of the audit; and

e. sufficient staff, supervisors, and specialists with adequate collective professional competence and other resources are available to conduct the audit and to meet expected time frames for completing the work.

But we are not done with the major topics in the performance audit chapters! There are two more things I need to tell you about: one is the requirement to understand the nature and profile of the program during audit planning and the other is audit documentation.

Major Topic #5: Nature and Profile of the Program

The GAO includes two lists of things you want to understand about the program in order to plan your audit. One list is a “should” list and the other is a “may” list. That means that you have to understand what is in 8.36 and you can “consider” understanding the items in the list at 8.38.

8.36 Auditors should obtain an understanding of the nature of the program or program component under audit and the potential use that will be made of the audit results or report as they plan a performance audit. The nature and profile of a program include:

a. visibility, sensitivity, and relevant risks associated with the program under audit;

b. age of the program or changes in its conditions;

c. the size of the program in terms of total dollars, number of citizens affected, or other measures;

d. level and extent of review or other forms of independent oversight;

e. program’s strategic plan and objectives; and

f. external factors or conditions that could directly affect the program.

Again, notice that 6.13 is a list of things you SHOULD understand about the program. The word “should” indicates a requirement that is not optional.

And then, in 8.38, the GAO lists things you “may” want to understand about the program. This list is optional.

8.38 Obtaining an understanding of the program under audit helps auditors to assess the relevant risks associated with the program and the effect of the risks on the audit objectives, scope, and methodology. The auditors’ understanding may come from knowledge they already have about the program or knowledge they gain from inquiries, observations, and reviewing documents while planning the audit. The extent and breadth of those inquiries and observations will vary among audits based on the audit objectives, as will the need to understand individual aspects of the program, such as the following:

a. Provisions of laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements: Government programs are usually created by law and are subject to specific laws and regulations. Laws and regulations usually set forth what is to be done, who is to do it, the purpose to be achieved, the population to be served, and related funding guidelines or restrictions. Government programs may also be subject to contracts or grant agreements. Thus, understanding the laws and legislative history establishing a program and the provisions of contracts or grant agreements is essential to understanding the program itself. Obtaining that understanding is also a necessary step in identifying the provisions of laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements that are significant within the context of the audit objectives.

b. Purpose and goals: Purpose is the result or effect that is intended or desired from a program’s operation. Legislatures usually establish a program’s purpose when they provide authority for the program. Audited entity officials may provide more detailed information on the program’s purpose to supplement the authorizing legislation. Audited entity officials are sometimes asked to set goals for program performance and operations, including both output and outcome goals. Auditors may use the stated program purpose and goals as criteria for assessing program performance or may develop additional criteria to use when assessing performance.

c. Internal control: Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved. Internal control comprises the plans, methods, policies, and procedures used to fulfill the mission, strategic plan, goals, and objectives of the entity.

d. Inputs: Inputs are the amount of resources (in terms of, for example, money, material, or personnel) that is put into a program. These resources may come from within or outside the entity operating the program. Measures of inputs can have a number of dimensions, such as cost, timing, and quality. Examples of measures of inputs are dollars spent, employee hours expended, and square feet of building space used.

e. Program operations: Program operations are the strategies, processes, and activities management uses to convert inputs into outputs. Program operations may be subject to internal control.

f. Outputs: Outputs represent the quantity of goods or services produced by a program. For example, an output measure for a job training program could be the number of persons completing training, and an output measure for an aviation safety inspection program could be the number of safety inspections completed.

g. Outcomes: Outcomes are accomplishments or results of a program. For example, an outcome measure for a job training program could be the percentage of trained persons obtaining a job and still in the workplace after a specified period. An example of an outcome measure for an aviation safety inspection program could be the percentage reduction in safety problems found in subsequent inspections or the percentage of problems deemed corrected in follow-up inspections. Such outcome measures show the progress made in achieving the stated program purposes of helping unemployed citizens obtain and retain jobs and improving the safety of aviation operations, respectively. Outcomes may be influenced by cultural, economic, physical, or technological factors outside the program. Auditors may use approaches drawn from other disciplines, such as program evaluation, to isolate the effects of the program from these other influences. Outcomes also include a program’s unexpected or unintentional effects, both positive and negative.

The optional list of things you may want to understand about your audit subject, Section 8.38, describes the components of a process. And from my experience, most audits involve looking at a process or two, so we should talk a bit more about it. A process has an input, an output, and an outcome. Let’s walk through some of the key terms in 8.38 using an example:

Inputs, Outputs, and Outcomes

Imagine you are trying to understand the process a county health clinic uses to vaccinate children.

We can measure the “inputs” into the process: the vaccines, the number of children in the county, and the number of nursing staff are all measures of the capacity of the clinic or what has to be input into the process to make it work. We can also look at another input – the efficiency or speed of the process. Examples of these efficiency inputs include measures such as the length of time it takes to schedule a child for an appointment, the waiting time for the family, the number of kids given shots per hour, and so on.

“Outputs” of the process count how many results we accomplished with our process. A good output measure for this process is the number of children vaccinated per week.

So now we have three elements of the county clinic flu vaccination process:

• INPUT: number of eligible children in the county = 7000 children

• EFFICIENCY INPUT: average length of visit = 45 minutes

• OUTPUT: number of children vaccinated per week = 150 children

But here is the kicker question: what is the “outcome” of this whole process? We want children to be healthy. We don’t want them to have the flu. So let’s add another aspect to the process, the OUTCOME metric.

• OUTCOME = percent of children avoiding flu illness = 92%

Add these measures to an understanding of the internal controls, the governing laws, the contract terms, and the program goals and you will have a solid understanding of the program. Having a solid understanding of the program allows you to better assess audit risk and design audit procedures.

Major Topic #6: Audit Documentation

I once had the pleasure of working with an audit supervisor who we’ll call Nancy. Nancy was very meticulous and had high expectations for her working papers.

Every working paper had to contain a description of the source, purpose, procedure, results, and conclusion of the individual working paper. It had to be uniquely titled and numbered. All cross-references had to be two-way (coming and going). Any tick marks had to be on Nancy’s approved list or approved by her in advance of use.

Some of her requirements were silly; some were very practical. Much of what she required had nothing to do with the standards and everything to do with making her life as a reviewer easier. And, if you have ever experienced the pain of reviewing working papers, you know how hard it is to follow an auditor’s trail without some of Nancy’s techniques!

However, what Nancy required of her audit team was not universally accepted throughout the audit shop.

On my next audit, I reviewed the work of an auditor named Andrew. I noticed that he did not apply any of Nancy’s rules.

So in my review notes, I told him that he needed to cross-reference; he needed to put source, purpose, procedures, results, and conclusion on every working paper; and he needed to stamp every page ¼ inch from the top right corner! Andrew responded, “Who says I need to do that? “ I sheepishly replied, “Nancy.” He said, “Nancy is not on this audit. I’m not doing all that stuff.”

Then I said, “Well, if you aren’t going to listen to Nancy, you should at least follow audit standards.” Wily Andrew said, “Sure. If it is in the standards, I’ll do it.” So I grabbed the Yellow Book and searched for something that would back up my argument, but, you guessed it, the standards only supported some of my review comments. Andrew was very pleased to find out that the location of the working paper stamp and the use of standardized tick marks was not in the standards.

However, the standards do say that you have to document the following:

• Nature, timing, extent, and results of audit procedures performed

• Source of evidence

• Conclusions reached

• Objective, scope, and methodology

• Work performed and evidence obtained to support significant judgments and conclusions

• Descriptions of transaction and records examined

• Evidence of supervisory review of evidence that supports findings, conclusions, and recommendations contained in the audit report

8.132 Auditors must prepare audit documentation related to planning, conducting, and reporting for each audit. Auditors should prepare audit documentation in sufficient detail to enable an experienced auditor, having no previous connection to the audit, to understand from the audit documentation the nature, timing, extent, and results of audit procedures performed; the evidence obtained; and its source and the conclusions reached, including evidence that supports the auditors’ significant judgments and conclusions.

8.133 Auditors should prepare audit documentation that contains evidence that supports the findings, conclusions, and recommendations before they issue their report.

8.135 Auditors should document the following:

the objectives, scope, and methodology of the audit; the work performed and evidence obtained to support significant judgments and conclusions, as well as expectations in analytical procedures, including descriptions of transactions and records examined (for example, by listing file numbers, case numbers, or other means of identifying specific documents examined, though copies of documents examined or detailed listings of information from those documents are not required); and supervisory review, before the audit report is issued, of the evidence that supports the findings, conclusions, and recommendations contained in the audit report.

So, because I was able to back up some of my review comments with Yellow Book requirements, Andrew played along and improved his working papers, but not to my full satisfaction. I had to dismiss the rest of my brilliant comments about cross-referencing, tick marks, stamping each page, etc. I learned through working with Andrew that cross referencing and tick marks were made up by the auditing profession to keep the working papers manageable and reviewable – they are not mandated by the standards.

And on top of that, I learned that the Yellow Book standards allow for a wide variety of formats and styles. As long as someone else can follow your logic, any format is fine.

But who do auditors ultimately have to please with our working paper documentation? Our supervisors, managers, quality reviewers, and peer reviewers. And this is where I got a tiny bit more traction with Andrew. I reminded him that I was just the first in a long line of anal-retentive auditors who would be looking at his working papers. And I told him I wasn’t even that bad compared to some of the reviewers I had experienced. Together, we cleaned his working papers up a little bit more by adding a few cross references and tick marks.

8.137 Audit documentation is an essential element of audit quality. The process of preparing and reviewing audit documentation contributes to the quality of an audit. Audit documentation serves to (1) provide the principal support for the audit report, (2) aid auditors in conducting and supervising the audit, and (3) allow for the review of audit quality.

SPPRC

One of Nancy’s expectations is a favorite of mine, too – the SPPRC. SPPRC stands for source, purpose, procedure, results, and conclusion. I teach auditors how to use the SPPRC in most of my classes because it helps us comply with the GAO’s audit documentation requirements.

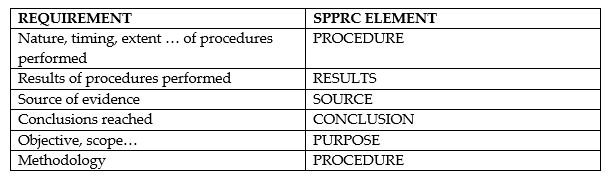

On the left side of the matrix below, I have listed most of the documentation requirements from the Yellow Book that we just covered. On the right, I have listed one of the components of SPPRC to show how they help us satisfy our compliance with the standards.

What do all these elements mean? Here are the questions that each element should answer:

• SOURCE: Where did you get the evidence on the working paper? Who gave it to you? What was the chain of custody of the evidence? What is the nature of the evidence? How can you get to the evidence again?

• PURPOSE: What question does this working paper seek to answer? Why was this working paper created and why was this work done? What program step does it satisfy?

• PROCEDURES: What did you do on this working paper? What methodology did you use? What were the detailed steps and procedures you performed? Go into a lot of detail here!

• RESULTS: What did the procedures yield? What were the results of applying the methodologies? This should contain the same terms and mirror the procedure element. You also want a lot of detail in this section.

• CONCLUSION: What is the answer to the question posed in the purpose? Was the program step satisfied? What did you do with any issues you found? Did you take the issues to a finding or a point disposition sheet?

Did you notice any link among the elements? If you do it right, the purpose and conclusions match, and the procedures and results match. This proves your clear thinking and supports your logical conclusions.

Here is a simple example:

• SOURCE: Student files maintained in the Student Financial Aid Office by Jane Doe. Tested fall semester 2004 students.

• PURPOSE: To determine whether students receiving federal student financial aid are eligible. To satisfy program step 2 at A-PGM.

• PROCEDURE: Sampled 72 files out of a population of 13,500 files. Examined each file to determine if the proper paperwork was in the file and that the student met federal eligibility requirements. The attributes tested are as follows:

Attribute 1

Attribute 2

Attribute 3

Attribute 4

• RESULTS: Out of all attributes tested on 72 files, we only noted one error. The student had failed to initial one of the pages of the financial aid application.

• CONCLUSION: Students receiving financial aid are eligible. The one error noted is not significant and we will not take it to the report.

What’s Next?

We will address the minor themes from the engagement chapters in the back of the Yellow Book in the next chapter entitled “Minor themes.”

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: