GAO Green Book, GAO Yellow Book … will the Government Accountability Office (GAO) never cease creating books with colored covers? Next thing you know, the GAO will come out with a Purple Book!

The GAO Green Book’s formal title is Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government. The GAO Yellow Book is also known as Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS).

Are you sleepy after reading those long titles? If you are like me, you are grateful for the simpler, color-oriented monikers of these important pieces of professional government literature.

What is the purpose of the GAO Green Book?

The GAO Green Book presents a comprehensive model that professionals can use to both create and audit internal controls.

The latest GAO Green Book was published in 2014 and is available online here.

COSO and the GAO Green Book are the same thing… from two different angles

As we will see, from the brief history of both the COSO model and the Green Book described below, the COSO model was initially created to strengthen internal controls in the corporate realm and the Green Book was initially created to strengthen internal controls in the government realm.

It took almost 40 years (!), but through a series of scandals, revisions and Congressional directives, the COSO model and the Green Book are finally aligned!

The GAO created the first Green Book in 1983

The GAO is the legislative auditor for the federal government.

In addition to auditing federal agencies and reporting the results back to Congress, the GAO also advises executive agencies on how to make government more efficient and effective.

As a matter of fact, the Federal Managers Financial Integrity Act of 1982 required the Government Accountability Office to establish standards for internal controls.

The GAO made its first efforts toward creating a standard for internal controls the following year in 1983. Then they plunked an emerald green cover on it and dubbed it the Green Book.

In the opening letter to this first version of the GAO Green Book, the Comptroller General of the GAO said:

In the past decade, numerous situations came to light that dramatically demonstrated the need for controls as the Government experienced a rash of illegal, unauthorized, and questionable acts which were characterized as fraud, waste, and abuse. It is generally recognized that good internal controls would have made the commission of such wrongful acts more difficult. Consequently, increased attention is being directed toward strengthening internal controls to help restore confidence in Government and to improve its operations.

Preach it, Comptroller! Unfortunately, as you know, fraud, waste and abuse in government are still going strong 40 years later.

Congress pushed for better controls in 1977, and the Treadway Commission was formed

Shortly before the passage of the Financial Managers Financial Integrity Act, it wasn’t government shenanigans but corporate misdeeds that had seized the attention of Congress.

In 1977, Congress enacted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) as a result of 400 US corporations admitting that they had made questionable or illegal payments to foreign officials as part of conducting business in other countries.

In response, the Treadway Commission, was formed in 1985 to inspect, analyze, and make recommendations on fraudulent corporate financial reporting.

The COSO Report was issued in 1992

As a result of the Treadway Commission’s initial report on the causes of the scandal, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) was formed to act on findings of the Treadway Commission report. The report identified inconsistent and ineffective auditing as one of the contributing factors to fraudulent financial reports.

The Committee was made up of the Institute of Internal Auditors, the AICPA and many other accounting and auditing organizations and they were charged with digging deeper into the issues surrounding the creation of corporate financial reports.

In turn, the Committee retained Coopers & Lybrand, a major CPA firm, to study corporate financial reporting and to create a report on controls. The resulting report was titled Internal Control – Integrated Framework and was issued in 1992.

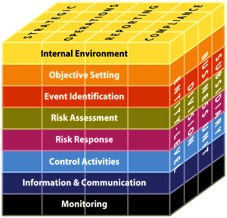

In this report, for the first time, we were all introduced to the internal controls cube that most US auditors use in their work today.

Over time, the COSO model, as it came to be called, was integrated into various auditing standards including the American Institute of CPAs auditing standards, the GAO’s Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (the aforementioned Yellow Book), and the Institute of Internal Auditor’s professional literature.

So, we auditors dutifully put the COSO model into our tools and then went about our normal business. In other words, most auditors didn’t pay that much attention to either model. And this came back to bite us.

SOX renewed interest in the COSO model in 2002

But shenanigans, of course, continued – model or no model. So after a pate of corporate financial scandals (Enron, WorldCom, etc.) at the turn of the century, Congress again turned their attention to the auditors and asked why the auditors didn’t catch these frauds. “Don’t you have an internal control model to follow now?” Congress asked.

Unsatisfied with the audit community’s response, Congress again acted to stamp the bad behavior out and passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (frequently referred to as SOX) in 2002.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires that auditors and leaders of publically traded companies in the United States certify that the internal controls over financial reporting are effective.

Most corporations and auditors used the COSO model as the framework to guide this assessment.

The COSO model evolved into the ERM

Naturally, the more the model was used, the more practitioners saw opportunities for improving the model.

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and other important members of the Committee cataloged these flaws and decided to straighten up the model. In 2004 this improved version of the model was published and renamed the Enterprise Risk Model or ERM.

As you can see from comparing the original cube to the ERM cube, the ERM cube is more detailed, especially when it comes to the components on the face of the model. While the Enterprise Risk Model did inform the 2013 revision of the COSO model, the COSO organization opted to limit the components on the face of the model to the original 5.

The COSO model and report were revised in 2013.

The original 5 component COSO model was revised in 2013, more than 20 years after its initial creation.

The 2013 revision didn’t alter the graphic of the cube very much (for instance, the side of the cube now uses the term “division” instead of “unit”).

But significant revisions were made to the format of the text of the report. And thank goodness, because the original 1992 COSO report employed lengthy complex paragraphs that were hard to read and decipher to explain key concepts.

The 2013 version mercifully breaks each of the five elements on the face of the cube into 17 principles, and then these principles are further broken into 81 points of focus.

Breaking down the original complex narrative into smaller, more digestible chunks makes the document much easier to scan and, thus, to use.

The 2013 version of the COSO model is available online for $99-270, depending on whether you want a piece of the document or the entire set of literature. But before you go and buy it, wait and read the next paragraphs!

The GAO published the Green Book in 2014

In September 2014, the GAO revised the Green Book based on the 2013 COSO model (remember, they originally published the Green Book in 1983!). The GAO essentially copied the 2013 version of the COSO model word-for-word and because they are the federal government, they didn’t have to pay the COSO organization to use their work!

And that leads me to my favorite feature of the Green Book: because this version of the COSO model is published by the federal government and shared online, it is absolutely free! In case you missed the link to this free resource before here it is one more time.

It took 40 years, but they made it!

Yes, it took a long time and a few scandals and Congressional directives, but now the COSO model and the GAO’s Green Book are – essentially – the same thing. Bravo, guys!

How well do you know the GAO Green Book? Take this simple quiz to find out

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: